D-Day Plus 60 Years

By Bruce L. Felknor

When Dwight Eisenhower outlined his intentions for the Normandy Invasion, the list began:

- Land on the Normandy Coast.

- Build up the resources needed for decisive battles in the Normandy-Brittany region.

But the resources were in England -- troops, tanks, artillery, ammunition, gasoline, supplies. Where to land them? Because existing port facilities (Le Havre and Cherbourg) were heavily defended and impossible to seize quickly, Eisenhower took another route, which he described as "a project so unique as to be classed by many scoffers as completely fantastic. It was a plan to construct artificial harbors on the coast of Normandy.

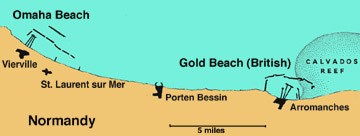

The English Channel Normandy beachhead The north shore of Normandy's Cotentin Peninsula juts westward into the Atlantic at the widest part of the English Channel. Churchill called it a "fifty-mile half-moon of sandy beaches," a hundred miles south of Brighton and Portsmouth.

Five landing sites had been selected on 21 miles of that sandy crescent, the American Utah and Omaha beaches on the west and the British and Canadian Gold, Sword, and Juno beaches to the east.

But that broad expanse of sand presented formidable obstacles to landing there. The ports at either end, Le Havre and Cherbourg, were massively fortified, and the beaches and other major ports, but expected lighter armament along the beaches. Even so, the beaches selected ended at a line of bluffs studded with German artillery.

Moreover, that part of the channel was notorious for bad weather. May was the earliest that a few weeks of fairly decent weather could be hoped for. And perhaps worst, 21-foot tides rose and fell there twice a day.

Winston Churchill had addressed that problem in a May 30, 1942, memo:

Piers for Use on Beaches. . . . must float up and down with the tide. . . . Let me have the best solution. . . . Don't argue the matter. The difficulties will argue for themselves.

The artificial harbors were secretly built in parts -- which German intelligence took to be for blocking their seaports, and towed into position by U.S. merchant seamen in a flotilla of tugs, where they were sunk in place. [A more detailed account is in chapter 23 of my "U.S. Merchant Marine at War 1775-1985."]

These miraculous port facilities would be placed at Omaha and Utah beaches for U.S. landings, and to the east for British and Canadian forces landing at Gold, Juno, and Sword beaches. In combination these harbors would be twice the size of Gibraltar. Through them in a few days would pass the men and machines of history's greatest amphibious operation--156,000 men with all their trucks and tanks and artillery pieces, and food and fuel and ammunition.

Tempestuous weather postponed D-Day from May until June 6. Before dawn, parachutes and gliders began landing two airborne divisions behind German lines on the peninsula. And the fantastic harbors to land their seaborne counterparts began to take place. During the few days of their construction Allied troops stormed the beaches from LCIs and LCTs with heavy air cover and artillery support from warships in the channel. Behind the guns a massive armada of freighters and troopships--all sailed by merchant mariners--clogged the channel awaiting the new harbors.

The Harbors: Operation Mulberry

The tidal pattern demanded a structure where ocean-going freighters could tie up even at low tide and discharge cargo into smaller craft to be ferried ashore.

The region was susceptible to horrendous and unpredictable weather, featuring wicked winter storms and ferocious summer gales. Constant heavy swells from the north demanded breakwaters.

A sheltered transfer point was needed for LSTs to transfer tanks or trucks to smaller LCTs which could land them on the beach--or on a pierhead at a causeway where they could be driven ashore.

Larger freighters needed a pier where they could tie up to discharge cargo, or at least a sheltered anchorage where they could by lighter or their own cargo booms discharge into barges or smaller craft. A strong current along the shore required additional breakwaters right at the shore.

Code names abounded. The Normandy Invasion was Operation Overlord. The artificial harbors were Operation Mulberry. Its ingredients were these:

- Phoenix breakwaters with unloading docks on the lee side;

- Gooseberry, onshore breakwaters consisting of battered old freighters sunk in sheltering arcs;

- Lobnitz pierheads floating with the tide inside a steel frame anchored to the bottom, connected to

- Whale causeways to shore above the high tide mark;

- Bombardon, floating outer breakwaters;

- Rhino, ferries to transfer cargo from ships or Phoenix piers to the beach.

The Allied assault had to be secret; work on the harbors had to await the first landings and go on under fire. Before dawn on D-Day, while paratroopers and glider troops were silently descending behind the German lines on the Cotentin Peninsula, blockships assembled in the Firth of Lorne were on their way south, armed with the usual 3-inch dual-purpose gun forward and 40-mm antiaircraft guns aft, with six or eight 20-mm anti-aircraft guns in

between. The usual 4- or 5-inch anti-submarine stern guns were replaced with the

40-mm anti-aircraft guns, all manned, as usual at sea, by a navy gun crew. (Army gunners manned the guns on the Army Transport Service tugs.)A hundred Phoenixes with their flotation chambers were ready for tow--two tugs per Phoenix. Ten Lobnitzes, their long legs locked in the up position, awaited tugs. Towboats, 176 of them under several flags, awaited the signal. At the beach it took four tugs to maneuver each blockship into position and hold it there against the tide while it was sunk.

Tugs positioning a Phoenix at Normandy Lobnitz pier Whale causeway Aerial view of Normandy harbor

In the Channel approaches gathered six battleships, 23 cruisers, and 105 destroyers ready to sail south to neutralize the German shore batteries and send up an antiaircraft curtain. A thousand smaller warships were poised to sweep mines, neutralize German patrol boats, watch for periscopes, whatever was needed.Operation Mulberry began and continued under fire, and the most essential parts of the job, started on the evening of June 7, were completed on D plus 8, June 14--one day ahead of schedule. "It functioned so smoothly," Lester E. Ellison, first mate on an army tug recalled, "that on 14-18 of June inclusive, an average of 8,500 tons of cargo poured ashore over it daily." This exceeded the design quota of 5,000 tons by nearly 60 percent.

As soon as they were unloaded the merchant ships returned to English ports for another cargo, some making three round trips. This was during the height of the Buzz Bomb era, when the Strait of Dover was known to mariners as Doodlebug Alley for the low-flying V-1 bombs. Gun crews on several freighters succeeded in shooting down V-1s in port or en route.

The British artificial harbor functioned at its design capacity from D-Day plus four, but its early role was accumulating stores and not landing personnel or vehicles. Eventually, however, it handled about one-quarter of all British personnel put ashore in Normandy, continuing in service even after the major ports of Le Havre and Cherbourg had been opened. By July 31 it had landed more than 627 million tons of supplies. It was finally closed on October 31.

Traffic through a Gooseberry comprised of derelict cargo shipsThe Storm

Bad luck, in the form of a ferocious summer storm, the worst June gale in 40 years, blew in on June 19 (D plus 13). It came from the north, the worst possible direction, piling up the seas against the beaches, creating a barrier of surf no landing craft could penetrate intact.

In three days of unrelenting fury, it all but demolished the American harbor, tossing smaller vessels athwart the causeways and creating general wreckage. The spuds were ruined, and most of Mulberry A was left good for nothing but repair parts for the British harbor. The British port sustained heavy damage too, but, partly sheltered by the Calvados Reef, it was much less damaged than its American counterpart and it was quickly restored to service.

Waves breaking over the guntub of a sunken ship. Liberty ship is in the distance. Storm damage on Normandy beach In fact, the American Mulberry was a work in progress throughout its short life. It began receiving ships while its facilities were still being installed, and its installation as designed was never completed. But even as major elements were being destroyed by the storm, essential activity went on at both harbors. The SHAEF report previously quoted observed:

The harbours had been designed to insure against precisely this emergency; but unfortunately the sudden gale caught them before they were finished and before the whole of the breakwaters had been laid. Moreover, whereas we had taken the possibility of a summer gale into our calculation, this gale was of winter strength.

An extremely dangerous situation arose. The [Bombardon] breakwater broke up and ceased to give any protection. Both outside the harbours and within them there were ships in distress, ships dragging their anchors or whose anchors were already lost. These threatened further to damage the structure of breakwater and piers.

The American harbour was the worse hit. Great seas surged through the gaps torn in the breakwater, drove small craft ashore, and seriously damaged the piers. Caissons [Phoenixes] which had been breached by pieces of wreckage began to crumble away.

However, the harbour and separate "shelters" were already to a great extent performing the function for which they had been designed. A very large number of ships and craft found sanctuary under the lee of the blockships and within the harbour breakwaters. Ships in distress, which would otherwise have been lost with their valuable cargoes, were saved by the friendly shelter of the artificial harbours.

And for three days of appalling weather, while beach unloading was impossible and the Army's supply situation became extremely difficult, a small but very vitally important trickle of stores went ashore through the harbour. Even on the worst day of the gale, 800 tons of petrol and ammunition as well as many hundreds of troops, were landed at Arromanches over the pierheads. Next day, while the gale still raged, this was increased to 1200.Great damage was sustained by the American harbour, which lacked the useful shelter which the Calvados reef provided for the British; and to make matters worse many of the components--caissons and lengths of pier -- were lost or damaged while on tow in the Channel during the three days' gale.

In view of these heavy losses of material it was decided to discontinue work on this harbour, which was now less necessary in view of the capture of Cherbourg. The main structure of the British port had stood up well to the weather, and the harbour was completed--partly with material salvaged from the American one. The work of strengthening its breakwaters is still proceeding.

Meanwhile the port continues in full operation. Within its breakwaters Liberty ships and coasters discharge their cargoes into DUKWs ["Ducks"] and lighters; and against its pierheads other ships unload thousands of tons each day into lorries which carry the stores straight to the Army's dumps.

Through the two harbors came 73,000 U.S. and 83,000 British and Canadian troops.

As the SHAEF report put it, "For the first time in history, a harbour has been built in sections, towed across the sea, and set down, during a battle, on the enemy shore."

And be it noted: towed across the sea, and set down, during a battle, on the enemy shore by the gallant men of the United States Merchant Marine and Naval Armed Guard, and their British and Canadian counterparts.

Sources:

Eisenhower, Dwight D. Crusade in Europe: A Personal Account of World War II. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co.,1948

Felknor, Bruce L. (Editor) The U.S. Merchant Marine at War, 1775-1945. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1998

Photographs courtesy of Perry Adams

Maps adapted from National Geographic Magazine, May 1945 and Encarta Encyclopedia06/02/04