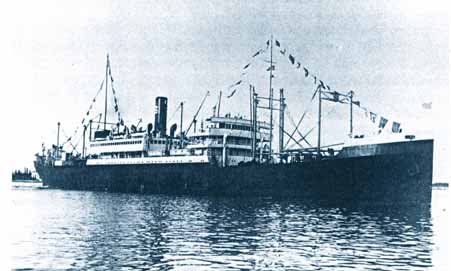

SS President Harrison: Master's Report to American President Lines

FROM: Master Orel A. Pierson

SUBJECT: Loss of Harrison, December 8, 1941Some time late in November 1941 we arrived at Manila, Philippine Islands, from the Pacific Coast via Honolulu, Suva and the Torres Straits. Here we were informed that we would proceed to Hong Kong to outfit as a transport and proceed to Shanghai together with the SS President Madison to evacuate the U.S. Fourth Marines.

On December 3rd we made a rendezvous off Formosa with four U.S. submarines and with their machine guns mounted ready for instant action, we proceeded to Olongapoo [Philippine Islands]. At this time, it was apparent to all that war was imminent. We noted, and reported, that Japanese Naval units and transports were steaming south in large numbers.

SS President Harrison Orel A. Pierson Left Manila on the morning of December 4, 1941, with a crew of 154 and one representative of the passenger department of American President Lines. On arrival at Chingwangtao we were to pick up around 300 Marines of the Peking and Tientsin Legation Guard and some 1400 tons of equipment and return to Manila.

The vessel was chartered by the U.S. Navy on a day to day basis for this purpose. We were under direct orders of Admiral Hart and were “on the drum” of the Cavite Naval Radio. In other words we were in constant contact, on a specified frequency and a secret call letter. The only actual orders I ever received were verbal “to proceed to Chingwangtao and bring out the Marines.”

Consider now the situation in the Far East. Tension was mounting, war or the possibility of it was on every man’s tongue The destination of the Harrison (though it was supposed to be a deep dark secret) was the talk of every hotel and bar room in Manila. The Japanese most certainly knew where we were going and for what reason. In fact, I was later informed by the Captain of a Japanese destroyer that “they knew all about our movements.”

All American ships bound for Chinese ports had been ordered to Manila and to my certain knowledge all British ships in North China waters as early as December 2nd had been ordered to proceed at full speed to Singapore. Proceeding north from Manila we again noted heavy Japanese shipping moving to the south.

SS President Harrison left Manila for Chingwangtao, but was captured near Shanghai Saddle and Shaweishan islands in vicinity of Shanghai

About 2:30 AM on the morning of December 7th we passed the North Saddles and set course for Shaweishan on the north side of the Yangstze estuary. Somewhere about 3:30 AM I received a message from Cavite that Pearl Harbor had been attacked. The show was on.

We were in hostile waters, surrounded on all sides by Japanese-held territory or Japan proper. The vessel was completely outfitted for the carriage of troops and if she fell into Japanese hands, could have been loaded and used for that purpose within a matter of hours against our forces in the Far East. I was bound and determined to use every means in my power to prevent this.

What to do? I have given some thought to the matter after leaving Manila. The first and obvious thing of course was to try and escape with the ship. Even though this might prove to be a hopeless move, we turned off immediately to the south/west hoping by some miracle we might work our way out through the islands south of Van Dieman Strait, make for the extreme north Pacific and eventually back to some Pacific Coast port. After informing the officers and crew as to what had happened we started to paint out the stack and superstructure hoping to get on as much grey paint as possible before we met up with any Japanese craft.

Being able to make about fifteen and one half knots we had not made many miles when daylight came and with it a Japanese plane with her bomb racks full. She signaled us to stop with a burst of machinegun fire and then after circling us flew off towards another ship that was coming up on the horizon.

This ship turned out to be the Nagasaki Maru a fast 22 knot mail boat on the Japan-China run. Apparently, he had been told to tail us and keep us under surveillance while he reported our whereabouts to the naval authorities in Shanghai. I knew this ship well and realized the futility of trying to escape from her. We were in no way afraid of her and as soon as we recognized her we got under way, but try as we would, could not lose her. As often as we changed course she did the same and stayed on our heels. I thought at one time of ramming her but she was smart enough to keep well clear of us while still keeping guard over us.

My plan was to run for the beach and send the ship up as high as possible at full speed hoping to accomplish this before any further ships made their appearance.

We started in the direction of Shaweishan as this was the nearest land and as we approached it I conceived the idea of sending the ship over the edge of it and ripping her bottom out completely. If we could achieve this, the vessel would go down completely and most surely be a total loss.

As we approached the island we sighted a Japanese destroyer making toward us under forced draft and the plane again returned over head. He did not open fire or drop his bombs - the reason I learned later, they wanted the ship intact.

It became a race as to whether we could make the island before the destroyer could intercept us. Five minutes before we struck we ordered the engineers out of the engine room leaving the plant wide open.

Shortly after 1:00 PM and making around sixteen knots, we struck the edge of the island in the vicinity of Number One Hatch on the port side. Being thoroughly familiar with the construction of these ships and their sturdiness I knew it would be useless to take the ship in head on. She would only have banged up her bow and most likely backed off and still floated. Several accidents in the past have proved this on vessels of this type.

The island is rounded and steep on the side we approached it from. She rode along the edge of the island for a considerable distance then heeled away over to starboard and rolled off. It turned out later we had ripped a hole in her 90 feet long but unfortunately she rolled off before reaching the engine room spaces.

We had kept our radio silent until close in then I gave the operator orders to open up and get a message away as to what we were doing. This message was received and acknowledged by a San Francisco shore station.

By now the plane had opened up with his machine gun and was strafing the ship presumably to stop us from using the radio. The plane made no attempt to strafe the boats in the water making for the island. The destroyer, running into shoal water, was feeling her way in to anchor.

I landed on the island with my boat crew thinking that all was well and all safely ashore. There I found that one boat had gone under the quarter and that the port propeller was still slowly turning over, due to steam within the engine itself not being fully exhausted, and that the boat had been capsized the crew thrown into the water and three of the men lost.

All the others had been picked up by the other boats including Mr. J. L McKay, Chief Steward, who had sustained several broken ribs. The Chief Engineer was suffering from a dose of fuel oil and from the shock of being immersed in the icy water. All others were apparently all right.

All of the men had climbed to the top of the island where the lighthouse is and the light keepers (Chinese) had turned one of the buildings over to them and they had set up a snack bar and were feeding the men.

Just as dark came on, a Japanese Naval Landing Unit (which is the same as our marines) from the destroyer landed on the island and made their way to the top bristling with guns and bayonets fixed. We threw the few revolvers we had into the bushes and surrendered.

First they destroyed the lighthouse radio station and then lined us all up and searched us for weapons - we had none - but anything we had such as money or papers were thrown on the ground and left.

The entire crew were then placed under guard on the island and I was taken off to the destroyer where I spent the night. I was taken in to the wardroom where I found the officers in a jubilant mood with the radio going full blast and as I soon learned reports coming in of the sinking of the Prince of Wales, the various ships in Pearl Harbor, etc.

Of course, the radio was in Japanese but several of the officers spoke excellent English and they certainly laid it on. They treated me very kindly, however and later the Commander made his appearance and after telling me how easy it would be for Japan to lick the world, broke out a bottle of Johnnie Walker Black label and treated everybody in the wardroom including myself.

Later I was given coffee and rice cakes, a bed was made up for me on one of the settees and I was made as comfortable as possible. In the morning I was fed the usual Japanese food and they even went so far as to find me a knife and fork to eat with.

Around 7 AM I was taken on deck -- a boat launched and I was told we would return to the Island - the boat got halfway to the island was ordered back to the destroyer -- from that moment on their attitude towards me changed entirely -- they became curt and abusive.

I am still at a loss to know the reason for their complete about-face unless they realized when daylight came that the Harrison was not the easy prize they expected it to be. As we left the destroyer, she was clearly visible a half mile away way down by the head and with a heavy list to starboard. When we got to the island the Japanese officer ordered the entire crew into the boats and back to the ship.

We found No. 1 hold partly flooded -- Nos. 2, 3 and 4 flooded into the Upper Tween Deck. No. 5 partly flooded and 12 feet of water in the engine room. After hatches were dry. We were able to relight the fires and get up steam and two men volunteered to dive into the icy water and open and close the necessary valves to pump out the engine room. We were solidly aground forward but afloat aft.

After trying to work the ship off with the engines (which would have no doubt caused her to sink in deeper water) and after breaking a couple of wires trying to pull her off with the destroyer, we suggested the possibility of lightening the ship by stripping her and throwing everything overboard. The Japanese agreed to this and we passed the word to sabotage everything possible. We threw at least a hundred thousand dollars worth of equipment over the side including motion picture equipment, pianos, furniture, stores, tarpaulins, hatches, and even the stronghooks.

When we suggested unshipping the booms and putting them over however they apparently decided it had gone far enough and put a stop to it. Realizing by now that they could not float her without assistance they sent to Shanghai for divers and salvage equipment -- at one time they had twelve divers on the job.

Then they sent to Japan for the Nippon Salvage Co. and they arrived with a complete salvage unit including a salvage master -- a Japanese born in Portland, Oregon and thoroughly familiar with salvage work. He went at the job in a more scientific manner and after 43 days of diving, patching and plugging they managed to get number one and two holds tight enough so that the heavy pumps could hold the water down. Then by flooding the after holds on the high tide of the month she floated off and was taken into Shanghai where she was placed alongside the dock and the divers, working in-between in the slack water plugged the holes enough to eventually get her to Japan and into a dry dock.

While on the rocks we faired fairly well for food but after entering Shanghai the ship’s food ran out and the Japanese took over the feeding. We went on very short rations then and I never did get a really full meal again until the war ended in 1945. We lived on the Harrison until the middle of March when the crew was released in Shanghai and the officers sent to a detention camp at Hongkew Park. None of the officers were ever released and sixteen of the crew died in Shanghai before the war ended.

I was taken to Japan the first of April 1942 to attend, as they said, a prize court. I was confined along with quite a few China Coast men in the Sasabro Naval Hall and until the middle of August, no person asked me a single question concerning the Harrison. One day, the Court, consisting of one man and his interpreter, asked me a series of routine questions. They informed me that they thought it would go very bad for me for the damage we had caused.

A few days later I was taken under guard and blindfolded (part of the time) to Zentsuji War Prison Camp on the Island of Shikoko. This was a Military Prison and I was sent there apparently because I held a Lt. Commodore’s commission in the U.S. Naval Reserve.

I arrived at Zentsuji on November 5, 1942 and remained there until June 23, 1945 when the camp was broken up and we were transferred to Rokuroshi Camp in the mountains of western Honshu. I remained a prisoner until finally liberated by the U.S. Armed Forces on September 2, 1945. I thus lost track of the President Harrison after 26th March 1942.

The story of my years in Prison Camps closely parallels that of any American held by the Japanese with all the heartaches, abuses, uncertainties and slow starvation accorded to them in the Military Prisons. I lost 85 pounds need I say more.

[The text above is an edited combination of two separate reports written by Captain Orel Pierson. The North China marines who were to be picked up by the President Harrison became Prisoners of War. Included in the cargo which was to accompany them were the fossils known as "Peking Man," whose whereabouts remain a mystery. Shaweishan Island no longer appears on maps, apparently removed as a hazard to navigation.]

Postscript:

The Japanese renamed the ship Kakko Maru. There were rumors that she was torpedoed and repaired, thus a name change to Kachidoki Maru. On September 12, 1944 while carrying 900 British Prisoners of War, the Kachidoki Maru was torpedoed by the U.S. submarine USS Pampanito (520 survivors). The Pampanito is now a museum ship, docked in San Francisco, home port of the SS President Harrison.

Sources:

San Francisco. California Oct. 11, 1945. Statement of O. A. Pierson Master of SS President Harrison. (Courtesy of Captain C. E. Gedney)

American President Lines Inter-Office Memorandum. To: Operating Manager - American President Lines. From: Master (Ex.) SS President Harrison (Courtesy of Captain C. E. Gedney)

Niven, John. American President Lines and Its Forebears, 1848-1984, Newark DE: University of Delaware Press, 1987

MAST, April 1944 and Sept. 1948

Grover, David H., and Grover, Gretchen G., Captives of Shanghai: Story of SS President Harrison, Napa, CA: Western Maritime Press, 1999

Asia map - http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/middle_east_and_asia/asia_pol00.jpg

Shanghai area map adapted from - http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/historical/blue_river_1912.jpgNames of SS President Harrison crew

01/28/05

www.USMM.org ©1998 - 2005. You may quote small portions of material on this website as long as you cite American Merchant Marine at War, www.usmm.org as the source. You may not use more than a few paragraphs without permission. If you see substantial portions of any page from this website on the Internet or in published material please notify usmm.org @ comcast.net