U.S. Merchant Marine in World War II

One way to understand the Second World War is to appreciate the critical role of merchant shipping... the availability or non-availability of merchant shipping determined what the Allies could or could not do militarily.... when sinkings of Allied merchant vessels exceeded production, when slow turnarounds, convoy delays, roundabout routing, and long voyages taxed transport severely, or when the cross-Channel invasion planned for 1942 had to be postponed for many months for reasons which included insufficient shipping....

Had these ships not been produced, the war would have been in all likelihood prolonged many months, if not years. Some argue the Allies would have lost as there would not have existed the means to carry the personnel, supplies, and equipment needed by the combined Allies to defeat the Axis powers. [It took 7 to 15 tons of supplies to support one soldier for one year.] The U.S. wartime merchant fleet. . . constituted one of the most significant contributions made by any nation to the eventual winning of the Second World War....

In the final assessment, the huge US merchant fleet... provided critical logistical support to the war effort... The Oxford Companion to WORLD WAR II

Casualties

The United States Merchant Marine provided the greatest sealift in history between the production army at home and the fighting forces scattered around the globe in World War II. The prewar total of 55,000 experienced mariners was increased to over 215,000 through U.S. Maritime Service training programs.

Merchant ships faced danger from submarines, mines, armed raiders and destroyers, aircraft, "kamikaze," and the elements. About 8,300 mariners were killed at sea, 12,000 wounded of whom at least 1,100 died from their wounds, and 663 men and women were taken prisoner. (Total killed estimated 9,300.) Some were blown to death, some incinerated, some drowned, some froze, and some starved. 66 died in prison camps or aboard Japanese ships while being transported to other camps. 31 ships vanished without a trace to a watery grave.

[Illustration shows SS Byron D. Benson torpedoed on 4/4/42 off North Carolina: 10 members of the crew of 37 lost their lives.]

1 in 26 mariners serving aboard merchant ships in World WW II died in the line of duty, suffering a greater percentage of war-related deaths than all other U.S. services. Casualties were kept secret during the War to keep information about their success from the enemy and to attract and keep mariners at sea.

Newspapers carried essentially the same story each week: "Two medium-sized Allied ships sunk in the Atlantic." In reality, the average for 1942 was 33 Allied ships sunk each week.

Bari - the Second Pearl Harbor

One of the most costly disasters of the war occurred in the Italian port of Bari, Dec. 2, 1943, during the invasion of Italy. A German air attack sank 17 Allied merchant ships with a loss of more than 1,000 lives. One of the five American ships destroyed that day was the SS John Harvey which carried a secret cargo of 100 tons of mustard gas bombs. When these exploded, hundreds of mariners, navy sailors and civilians were affected. Many died from the effects of the mustard gas.

[Illustration at right shows ships burning at Bari.]

The Massacre of the SS Jean Nicolet

The Liberty ship SS Jean Nicolet was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine on July 2, 1944, off Ceylon (Sri Lanka). She had a 41-man crew, plus 28 Armed Guard, 30 passengers and an Army medic. All survived the explosion. They were taken aboard the sub and their lifeboats and rafts were sunk. With their hands tied behind their backs they were forced to sit on deck. Japanese sailors massacred many with bayonets and rifle butts. Thirty survivors were still on deck with their hands tied when a British plane appeared. The sub crash-dived, washing the survivors into the sea. Only 23 were rescued.Names of Mariners Killed in World War II

Ships attacked before Pearl Harbor

Ship Sinkings by Region

The Battle for Control of the Atlantic

In his book "The Second World War," Winston Churchill stated: "The only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-Boat peril."

The Battle of the Atlantic was not what one usually thinks of as a "battle," since it did not take place in one location over a limited period, such as the Battle of the Bulge. It was a Battle for CONTROL over shipping in the Atlantic and lasted from September 1939 until May 1945. Germany's submarines (U-Boats) tried to sink merchant ships faster than the Allies could build them. Starting in 1940, through the middle of 1942, U-Boats were very successful - they sank more ships than were built.

Statistics about Allied losses of men and ships in the Battle of the Atlantic vary widely. Battle of the Atlantic Statistics

Convoys

Germany used the U-Boat (Unterseeboot) to great advantage early in World War I to isolate Great Britain from much of its food, oil, and raw materials. Several days before the outbreak of World War II, German U-Boats were already on the prowl against supply ships, and again Britain instituted convoys, which had been so successful in limiting losses 20 years earlier.The downside to convoys were the delays involved: waiting to assemble; taking a common, but often longer route; reducing speed to match the slowest ship, and delays in unloading because of congestion. This cut cargo-carrying capacity by one-third.

U-Boat Happy Time

In September 1939, Germany had 46 U-Boats. By the end of the War, 863 U-Boats were commissioned. At first, the U-Boats went out individually, but changed tactics in September 1940, to travel at night in "wolf packs" preying on merchant ships. This was their first "Happy Time."Eventually, the British beefed up convoy escorts and air support, and losses decreased. As soon as Germany declared war on the United States (Dec. 12, 1941), U-Boats headed for the U.S. Atlantic seaboard. From January to May 1942 was "Happy Time" again.

For inexplicable reasons, the U.S. did not arm the ships, nor provide escorts or air cover, nor organize convoys along the Atlantic or Gulf Coasts or in the Caribbean. Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King was responsible for this inaction. The U.S. Government did not order a blackout of seacoast cities until June 1942, leaving ships silhouetted against the shoreline. Allied ships were "sitting ducks" for the well-armed U-Boats lurking in U.S. coastal waters. U.S. beaches soon became littered with bodies and burned-out ships.

The story of SS Oklahoma and SS Esso Baton Rouge and the Oklahoma's unnamed dead, identified and honored in 1999. [Courtesy of The Atlanta-Journal Constitution]

1942 was the most successful year in U-Boat history, with 1,200 Allied ships sunk. (Middlebrook, Convoy) Other sources count 1,664 ships sunk, 1,097 of them in the North Atlantic. (Albion & Pope, Sea Lanes in Wartime) Between December 1941 and May 1942, the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard sank only two U-Boats.

Late in the spring of 1942, the War Shipping Administration finally organized trans-Atlantic convoys, with American, Canadian, and British escorts to improve the odds for the slow, lightly armed ships. Along the seaboard, ships were herded into port overnight. However, the situation for merchant ships was still poor.

Germany often had advanced knowledge of ship movements through spies and interception of radio messages about planned convoy routes and cargoes, but even without that information, submarines would line up about 15 miles apart across the expected convoy route. The first to spot the convoy would fall in a few miles behind and signal for the rest of the "pack" to assemble for the night attacks. Groups of U-Boats would stage simultaneous attacks from several directions. A "classic" attack was to come in submerged ahead of the convoy, allow the escorts to pass, and to come up to periscope depth in the middle of the convoy!

Many battles between U-Boats and convoys took place in the "Air Gap," a wide band of the North Atlantic which was not patrolled by aircraft and took 4 or 5 days to cross by convoy. Airplanes could spot submarines at great distances and drop depth charges to keep the subs away from the convoy, so submarines rarely attacked while aircraft protected a convoy. The U.S. had 112 long-range aircraft which could have provided air cover across the entire Atlantic, but chose to put all 112 in the Pacific.

As U-Boat successes mounted, the British ignored internal suggestions to bomb the U-Boat ports in St. Nazaire and Lorient on the Bay of Biscay, France, concentrating on German factories instead. By October 1942, when U.S. and British Air Forces finally bombed the submarine pens, they had been reinforced with 12 feet of reinforced concrete. The Allies dropped 40,000,000 pounds of bombs, lost over 100 planes, and not a single U-Boat was damaged.

Greatest Convoy Battle of All Time

In March 1943, Convoys HX229 and SC122 with 88 merchant ships and 15 escorts, were bound for Europe from New York, via Halifax, on parallel courses. In mid-Atlantic, they were relentlessly attacked by 45 U-Boats operating individually and in "wolfpacks," who fired 90 torpedoes, sinking 22 ships, and resulting in 372 dead. Germany called it the "greatest convoy battle of all time."

British and U.S. escorts used 298 depth charges to sink one German submarine and to damage several others, while suffering 1 casualty. Escort vessels were overwhelmed by the simultaneous need to hunt submarines and pick up survivors.

Convoy HX229

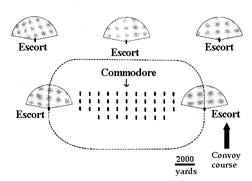

The fan-shaped areas in the diagram of Convoy HX229 indicate radar range of escort vessels. Speedier escorts sailed back and forth along the perimeter of the convoy, like sheepdogs guarding their flock.

The grouping of merchant ships is approximately 5 miles wide; the most valuable cargo such as airplanes, gasoline, ammunition, and troops was centered in the convoy. Stragglers from convoy faced almost certain destruction by the "wolves."

Convoy SC122 averaged 6.9 knots across the Atlantic, while U-Boats averaged 17.5 knots on the surface, 7 knots submerged.

In the accompanying diagram, Convoys HX229 and SC122 are represented by rectangular areas with their direction of travel shown. The dark dots represent submarines, shown arranged in their groups "Sturmer," "Dranger," and "Raubgraf." One submarine is shown tailing Convoy HX229; some submarines are refueling at the two tankers indicated by the "T." (Diagrams adapted from Middlebrook: Convoy)

SS William C. Gorgas

The SS William C. Gorgas, sailing in convoy HX228 from New York to Liverpool, was one of 120 ships torpedoed and sunk in March 1943. The torpedoes killed the engine room crew, but missed the 900 tons of TNT she was carrying. The survivors who were picked up by HMS Harvester (British escort) were torpedoed again that same evening. Only 12 of the 70 mariners and Armed Guard on board the SS William C. Gorgas survived.Ordeal of Convoy NY119

One of the most daring and unusual Atlantic convoys left New York for England in September 1944. It was made up of a variety of sea-going tugs, small harbor tugs, yard tankers, and railroad car floats with wooden barges mounted on top. These were owned by the U.S. Army and were desperately needed in the bombed-out harbors of France. The U.S. Navy, with a few destroyer escorts and other small vessels, managed to herd this slow-moving armada to Falmouth, England, via the Azores Islands. The convoy, which took 30 days, encountered a violent storm in the English Channel, losing a large number of ships and 19 mariners in this dare-devil crossing.

Murmansk Run: Cold, Deadly Voyages

The most deadly of 40 convoys sent to Murmansk, USSR, above the Arctic Circle on the Barents Sea, was PQ17 which left Iceland carrying cargo worth $700 million. PQ17 comprised:

- 33 merchant ships plus 1 oiler to refuel the escorts

- 3 rescue ships

- 5 destroyers

- 3 corvettes

- 3 minesweepers

- 4 anti-submarine trawlers

- 2 anti-aircraft ships

- 2 submarines

A large battle fleet of British and U.S. Navy ships sailed on a parallel course. The Allies hoped to lure the Germans into an uneven battle. But when the British Admiralty mistakenly thought the German battleship Tirpitz with firepower superior to the British ships and the battle cruiser Scheer were on their way to intercept PQ17, the Admiralty ordered British and American warships to abandon the convoy to avoid heavy Navy losses. They told the convoy to: "Scatter fanwise. Proceed to destination at utmost speed." The merchant ships were thus abandoned to almost certain destruction, and an icy death for their crews.

[Illustration of mariners from The Battle of the Atlantic, Barrie Pitt, Alexandria, Virginia: Time-Life Books, 1977]

The 5 destroyers were ordered to join the fleeing Navy ships. Some of the escorts ran for safety; many bravely tried to help the merchant ships the remaining 700 miles to safety. Between July 4 and July 14, 1942, Nazi torpedo-bombers and U-Boats launched repeated, devastating attacks on the lightly armed ships.

The Germans wanted to stop Allied aid to the Soviet Union and hoped that 100% annihilation of a convoy would do it. PQ17 was chosen for the "Knights Move."

Only 11 of the 34 merchant ships reached port. Twenty-four were sunk, along with 153 mariners and Armed Guard, 250,000 tons of war materiel, including 3,500 trucks, 200 aircraft and 435 tanks. Lifeboats brought some mariners to German-occupied Norway where they became POWs. Some survivors spent up to 3 weeks on rafts and open lifeboats and lost limbs to frostbite.

Ironically, the German battleships never did put to sea. Winston Churchill so aptly said, "PQ17 was one of the most melancholy episodes of the war."

Through the Murmansk Run, the United States supplied the Soviet Union with 15,000 aircraft, 7,000 tanks, 350,000 tons of explosives, and 15,000,000 pairs of boots. American boots made a difference on the Eastern Front, especially during the harsh winters.

List of American Ships on the Murmansk Run

Action in the South AtlanticOne of the most dramatic acts of heroism occurred Sept. 27, 1942, in the South Atlantic on the Liberty ship SS Stephen Hopkins. She came upon the heavily-armed German raider Stier, disguised as a neutral ship, and her escort, the Tannenfels. When the Hopkins refused to surrender, both vessels shelled her.

The Hopkins fought back valiantly. With his ship in flames and her stern gun-crew dead, engine cadet Edwin O'Hara, from the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy, fired the last five available shells, setting the Stier on fire. O'Hara, killed by shrapnel, and 40 others went down with the ship. The Stier blew up and sank. The 19 survivors of the SS Stephen Hopkins set off on a 2,000-mile, 31-day voyage to Brazil in a lifeboat during which four crewmen died.

Captain Paul Buck, O'Hara and three officers were given the Distinguished Service Award posthumously. The Hopkins received the Gallant Ship Award. The U.S. Merchant Marine Academy is the only Federal academy authorized to carry the Battle Standard Flag, by virtue of her 142 Cadets killed in action.

[Midshipman Edwin J. O'Hara, loading the last shell on the SS Stephen Hopkins.

Painting by W.M. Wilson, reproduced by permission of the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy]End of U-Boat Action

When Germany capitulated in May of 1945, Admiral Doenitz ordered the commanders of forty-three U-Boats then at sea to cease action and give themselves up, but it was not until August of 1945 that the last "Sea Wolf" made port. Of the 863 U-Boats commissioned, 784 were lost at sea or incapacitated in port.SS Black Point -- Last U-boat Victim of the War - May 5, 1945 off Point Judith, Rhode Island.

Merchant Marine in the PacificOn Dec. 7, 1941, the cargo ship SS Cynthia Olson was the first U.S. flag ship torpedoed by a Japanese submarine in World War II. The ship and all on board were lost about 1,200 miles west of the Pacific Coast. The tanker SS Emidio was sunk by a Japanese sub 18 miles off Crescent City, California on December 20, 1941.

The Japanese navy never targeted shipping in the Pacific, so the convoy system was used primarily during invasions. Hundreds of merchant marine ships shuttled men, food, guns, ammunition, and other supplies across the Pacific. 44 merchant ships were sunk at Pacific beachheads, countless others damaged by kamikazes, bombers, artillery, or torpedoes while they took part in every invasion.

"The men and ships of the Merchant Marine have participated in every landing operation by the United States Marine Corps from Guadalcanal to Iwo Jima -- and we know they will be at hand with supplies and equipment when American amphibious forces hit the beaches of Japan itself."

Lt. Gen. Alexander A. Vandegrift, U. S. Marine Corps CommandantSS Admiral Halstead

The SS Admiral Halstead was in Port Darwin, Australia on February 19, 1942 with 14,000 barrels of high octane gasoline when the Japanese launched heavy air raids on the port. After the first raid, military authorities ordered the crew to leave the ship. For 9 days, 6 of her crew voluntarily reboarded her each morning to take her away from the docks, and each night brought her back to discharge her precious cargo. They manned her two machine guns successfully -- the SS Admiral Halstead was the only one of the 12 ships in the harbor which was not damaged or destroyed.Battle for the Philippines

In October 1944 merchant ships delivered 30,000 troops and 500,000 tons of supplies to Leyte, during the invasion of the Philippines. They shot down at least 107 enemy planes during the almost continuous air attacks.In the Mindoro invasion of the Philippines, more merchant mariners lost their lives than did members of all the other Armed Services combined. Sixty-eight mariners and Armed Guard on the SS John Burke and 71 on the SS Lewis E. Dyche disappeared, along with their ammunition-laden ships as result of kamikaze attacks. The SS Francisco Morazon, also in the same convoy, fired 10 tons of ammunition defending herself. A majority of the merchant ships sunk in the Pacific were sunk by kamikaze suicide pilots.

Twenty ships loaded with troops and ammunition were anchored at Leyte fighting off the round-the-clock kamikaze attacks. Merchant mariners were fully involved working with the Armed Guard gun crews, rescuing soldiers from fiery decks below, and often assisting the Army doctors with the wounded. One kamikaze hit the SS Morrison B. Waite, starting fires among the Army trucks below. Able seaman Anthony Martinez went into the cargo hold to rescue several soldiers who were unloading the trucks, then dove overboard to rescue two soldiers who were blown into the water.

Commenting on the part the Merchant Marine played in the Mindoro Invasion, Gen. Douglas MacArthur said: "I have ordered them off their ships and into foxholes when their ships became untenable under attack. The high caliber of efficiency and the courage they displayed mark their conduct throughout the entire campaign in the Southwest Pacific area. I hold no branch in higher esteem than the Merchant Marine."

Mariners who participated in these invasions received veteran status in 1988 only after a long court battle!

List of U.S. Merchant Marine ships participating in Pacific Theater Operations and earning Battle Stars for their U.S. Naval Armed Guard crews

Operation Downfall - Planned Invasion of Japan

[Landing barges at Okinawa carry ammunition, fuel, and other supplies

from the cargo ships seen on the horizon. War Shipping Administration photo]Merchant ships delivered many of the 180,000 troops and over 1 million tons of supplies during the invasion of Okinawa while under attack from 2,000 kamikazes as well as other airplanes. The next invasion, OPERATION DOWNFALL, was to be the Japanese islands.

In April 1945 there were an estimated five million Japanese military, with nearly two million on the main islands. Japan's terrain was considered good for defense and difficult to attack. The invasion would be tougher than Normandy, Tarawa, Saipan, Iwo Jima or Okinawa.

The United States forces in the Pacific had suffered 300,000 battle casualties up to July 1st. The assault on Japan was predicted to kill and wound one million more Americans. Invasion plans involved nearly five million American soldiers, sailors, marines and coast guardsmen. Convoys carrying the troops and supplies to the landings in Japan would have to cross hundreds of miles of ocean on their way from the Marianas, the Philippines and Okinawa. Japan had 9,000 aircraft and 5,000 kamikaze ready for attacks on the invasion fleet.

The U.S. Merchant Marine was an essential part of this huge planned effort.

Dropping atomic bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki led to the signing of unconditional surrender on board the USS Missouri on September 2, 1945.

After the Japanese Surrender

While action by Japanese units continued in various areas throughout the Pacific, the U.S. Merchant Marine was given the job of transporting the surrendered armies back to Japan.The Merchant Marine also had to return the tired, wounded, and dead U.S. troops home, and to bring replacement forces and supplies for the Occupation. Arms and bombs had to be returned to the U.S.. In December 1945, the War Shipping Administration listed 1,200 sailings - 400 more than in the busiest month of the previous 4 years. 49 U.S. merchant ships were sunk or damaged after V-J Day with at least 7 mariners killed and 30 wounded.

Ships sunk after V-E and V-J Day

Merchant Marine in Every Invasion

The Merchant Marine on their Liberty ships, World War I vintage "Hog Islanders," and anything else that floated, took part in every invasion of World War II. Many Libertys had temporary accommodations for 200 troops and headed for the beaches under enemy fire with invasion barges in the rigging ready to lower.

[Ship unloading onto barge at Anzio, Italy, War Shipping Administration photo]

Allied invasions started in November 1942: North Africa, followed by Sicily, Salerno, Anzio, and Southern France. In the narrow Mediterranean, full of islands and peninsulas, ships always faced attack from land, as well as air and sea. They were attacked by airplanes, shore-based artillery, submarines, mines, frogmen, and glide bombs. During 9 days at Anzio, Italy, the Liberty ship SS F. Marion Crawford counted: 76 air attacks by 93 planes, and 203 near misses from shore artillery. The ship took 2 hits from 170 mm shells. Her crew hit 3 enemy planes.

The experience of a 13 ship convoy to Algeria in January 1943 was typical:

Junkers 87's [German planes] made torpedo runs at same time as a flight of dive bombers attacked. Liberty ship SS William Wirt, carrying aviation fuel, shoots down 4 bombers. A dud bomb landed inside her hold. One bomber crashes into Norwegian ship, which explodes and sinks. British ship carrying American troops torpedoed and sinks. Three waves of torpedo-bombers and high-level bombers stage attack. The Allies sink an Axis submarine. Torpedo-bombers and high-level bombers attack again; SS William Wirt, shoots one bomber down. Two more air attacks sink one ship. On the homeward leg, another air attack near Gibraltar.

Normandy Invasion

Ships and more ships, as far as the eye can see at Normandy beach. Note the large number

Liberty ships disgorging their cargo into small boats. This shows the part played by the

merchant marine in bringing the men and their equipment across the Channel for the invasion.

Barrage balloons protect the ships from attack by low-flying aircraft.

[War Shipping Administration photo]American mariners took part in the invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944. In the two years before the invasion, enormous quantities of war materiel were ferried across the U-Boat infested Atlantic to Britain by merchant ships. About 2,700 merchant ships were involved in the first wave of the invasion on D-Day, landing troops and munitions under enemy fire.

In Operation Mulberry, about 1,000 American mariner volunteers sailed 22 obsolete merchant ships (Blockships), to be sunk as artificial harbors at the Omaha and Utah beachheads. These ships, many of which had previously suffered severe battle damage, were charged with explosives for quick scuttling. They sailed from England through mined waters, set up in position under severe shelling from the Germans, and were sunk. Behind this breakwater, prefabricated units were towed in to handle the unloading of men and equipment.

American mariners also crewed many of the tugs which towed the huge concrete caissons across the English channel to be sunk with the Blockships. During the next year, at great risk, mariners continued to shuttle 2.5 million troops, 17 million tons of munitions and supplies, and a half million trucks and tanks from England to France.

American Merchant Marine at Normandy June 1944

We Deliver the Goods

There were three major groups that represented the U.S. in World War II. Our fighting forces overseas, our production force at home and the Merchant Marine and the Naval Armed Guard, the link between them. Each force was dependent upon the other. The Merchant Marine was responsible for putting our armies and equipment on enemy territory and maintaining them there.

Merchant ships delivered :

- Troops

- Ammunition, food, tanks, and winter boots for the U.S. and Allied infantry

- Bombs, airplanes, and their fuel

- Raw material needed to make all of the above

We Deliver the Goods Statistics from War Shipping Administration Report, January 15, 1946

Troops and Cargo Transported During World War II under U.S. Army Control

Quotess

During World War II President Franklin D. Roosevelt and many military leaders praised the role of the U.S. Merchant Marine as the "Fourth Arm of Defense."

General Quarters! All Hands to Battle Stations! Naval Armed Guard and Mariners worked as a team manning the guns during WWIIShip poster prohibiting diaries or other communications

Battle of the Atlantic Statistics

Allied Merchant Ship Losses 1939 to 1943. Press Release, Office of War Information, Nov. 28, 1944

War Shipping Administration List of Officials, Purpose, Creation, Activities

Troops and Cargo Transported During World War II under U.S. Army Control

Men and Ships of World War II

U.S. Maritime Service Training Organization01/31/07

www.USMM.org ©1998 - 2007. You may quote material on this web page as long as you cite American Merchant Marine at War, www.usmm.org, as the source. You may not use more than a few lines without permission. If you see substantial portions of this page on the Internet or in published material please notify usmm.org @ comcast.net